‘The Art of the Qur’an,’ A Rare Peek at Islam’s Holy Text

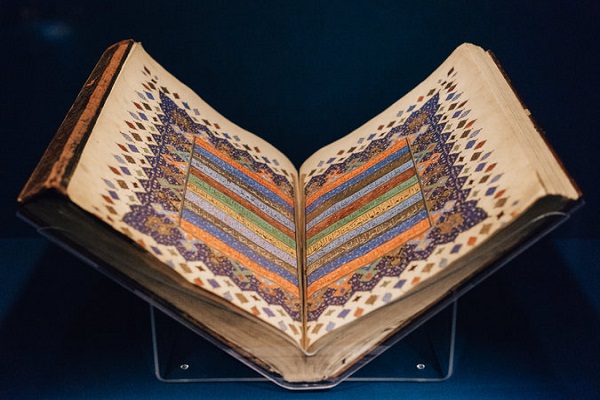

It’s a glorious show, utterly, and like nothing I’ve ever seen, with more than 60 burnished and gilded books and folios, some as small as smartphones, others the size of carpets.

Flying carpets, I should say. This is art of a beauty that takes us straight to heaven. And it reminds us of how much we don’t know — but, given a chance like this, will love to learn — about a religion and a culture lived by, and treasured by, a quarter of the world’s population.

The manuscripts, most on first-time loan from a venerable museum in Istanbul, date from the seventh to 17th centuries, and come from various points: Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Turkey. Some volumes are intact; others survive as only single pages, though so great is the Quran’s spiritual charisma that, traditionally, every scrap is deemed worthy of preserving. And the Sackler curators, Massumeh Farhad and Simon Rettig, give the material all the glamour it deserves, with a duskily lighted installation in which everything seems to glow and float, gravity-free.

The word Quran (or Koran) is derived from an Arabic verb for speaking from memory or reading aloud. And the book originated with the sound of a voice heard by a man named Muhammad ibn Abdullah [PBUH] near Mecca, the city in what is now Saudi Arabia. A trader by profession, he was in the habit of spending periods of reflection in a cave outside of town. On one visit, in A.D. 610, when he was 40, he heard a command, seemingly coming from nowhere, in Arabic:

Recite! In the name of thy Lord,

Who taught by the pen,

Taught man what he knew not.

Fearing for his sanity, he fled the cave. But he returned, and the voice, which belonged to the Angel Gabriel, spoke again, bringing a message from God. The message named Muhammad [PBUH] prophet of a new monotheistic religion and explained its tenets and beliefs to him. He began to share what he’d heard, but encountered violent resistance, and had to move to another city, Medina. The voice followed him there and would continue to speak until Muhammad’s [PBUH] death in 632.

By that point, the new religion, called Islam — “submission, surrender” — had found its footing and attracted followers, and the words Muhammad [PBUH] heard had been written down. With the prophet himself gone, and his closest companions aging, there was fear that the revelations would be lost. So a great effort of copying, collecting and collating began, and by the end of the seventh century, the Quran acquired something like a final shape.

A curious shape it is. About the length of the New Testament, the book has 114 chapters, or suras, all but one beginning with the same invocation: “In the name of God, the Merciful, the Compassionate.” Some chapters run several pages; others are just a few lines. Many of the shortest are urgent and rousing: They seem to record what Muhammad [PBUH] heard in those first hair-raising sessions in the cave. Yet they tend to come toward the back of the book, while longer, later passages — about communal practicalities and social justice — are placed up front.

And the pen, along with the voice, became the book’s primary medium. The physical act of copying the text was thought to bring blessings — baraka — to the writer.

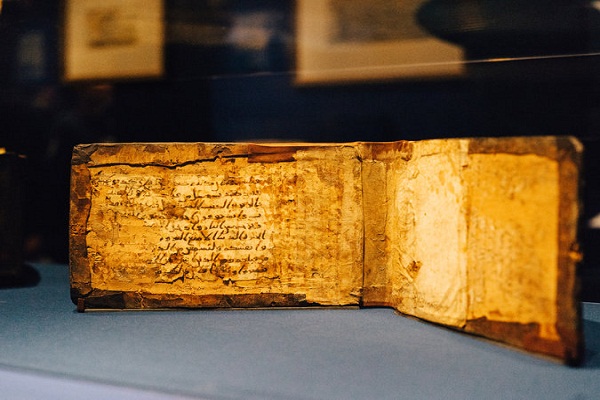

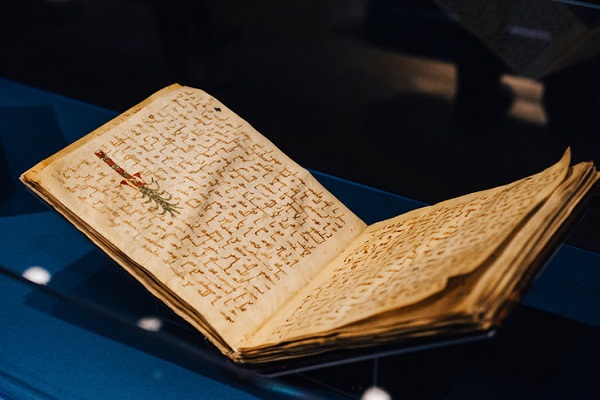

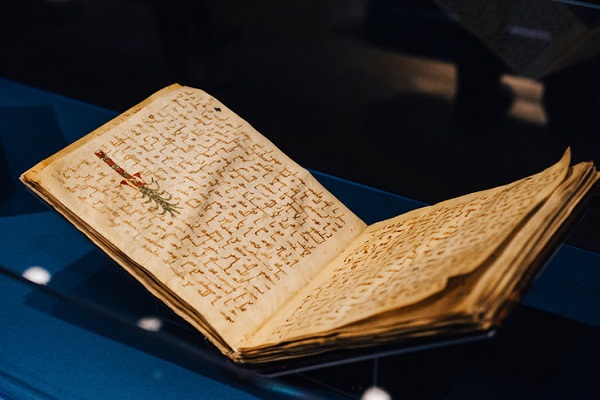

The earliest example in the show dated from the late seventh or early eighth century, and was found in the archives of the Great Mosque in Damascus. It’s a time-stained parchment folio covered almost edge to edge with Quranic passages. Written in an informal script, with chapter divisions barely acknowledged, it looks more like a personal letter than like a religious text.

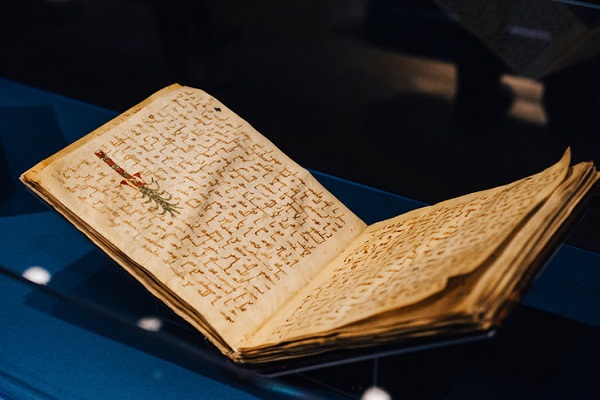

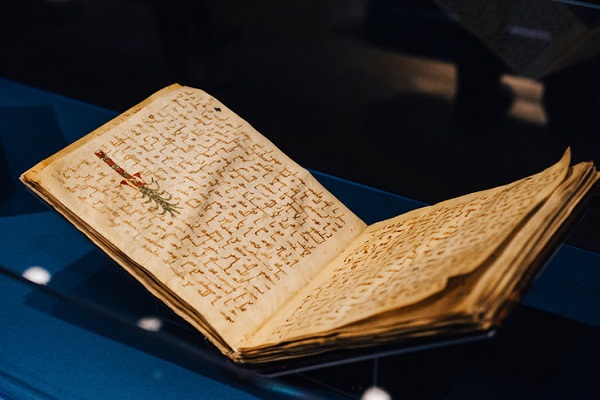

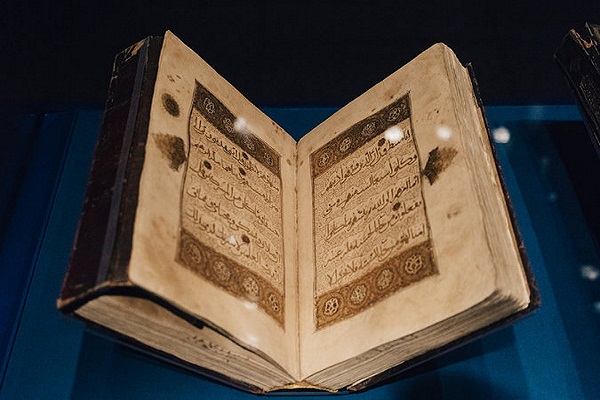

Over time, though, highly refined penmanship styles, visual equivalents to the cadences of the spoken word, were designed specifically for the Quran, and masters of those styles were revered as cultural stars. So wide was the fame of the 11th-century Baghdad artist Ibn al-Bawwab (“son of the doorman”) that his signature was routinely forged, as is the case with a Quran in the show that bears his name but was copied by someone else.

One of his 13th-century Baghdad successors, Yaqut al-Mustasimi, was comparably celebrated. When a Mongol army laid waste to the city in 1258, his life was spared so that he could work for the new rulers, which he did for years. Although very few genuine examples of his work are now known, the show has one.

Largely because of its Quranic association, calligraphy came to be regarded as the greatest of Islamic art forms, sacred or secular. Spilling out of books onto wall tiles, ceramic vessels, glass lamps, textiles, mosque domes and building facades, it was both a sensual and ideological unifier, totalizingly utopian in the way that Mondrian’s environmental Modernism would be.

Yet calligraphy was not the only elaborating gloss applied to the Quran. After the introduction of paper from China in the eighth century, copying the text on parchment — animal skin — fell into disfavor, and all kinds of experimentation came into play.

Multivolume Qurans — 30 volumes was a typical number, corresponding to the days of Ramadan — became more common as paper made them easier to produce, and compact one-volume versions gained in popularity. Size increased. The show has two pages from one of the largest Qurans on record. Probably made for the Mongol emperor Timur around 1400, they’re the equivalent of six-foot-high billboard advertisements for institutional power: the power of rulers, patrons, artists, religion, the Quran itself.

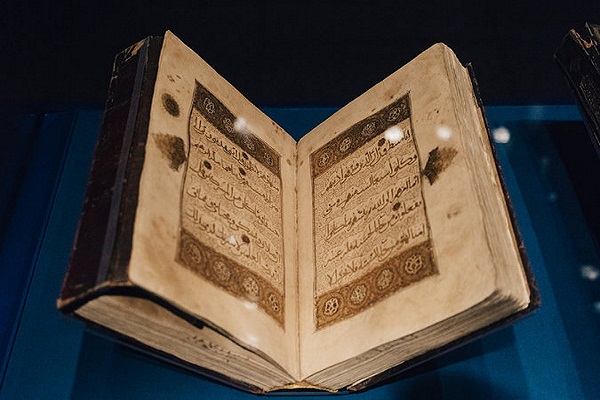

Over the centuries, the holy book became increasingly treated as an aesthetic object and a ritual instrument. Symbols were introduced to orchestrate the all-important recitation of its contents: indicators of where to pause, where to place emphasis, how to pronounce words. These signs, exquisitely painted, wreathed the text in networks of florets, medallions and arabesques, done in lapis-lazuli blue or light-catching gold.

Material preciousness became an end in itself, turning Qurans into prestige objects and political currency, valued as diplomatic gifts, as war booty and as pious, grace-earning donations to mosques and mausoleums. Many Qurans in the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts’ collection were transferred there from royal tombs at the turn of the 20th century, when Europe was plundering Turkey for art.

The impression of the Washington exhibition is of splendor, not just from book to book and page to page, but within individual pages, with their nested divisions, their lustrous ornaments and their sprouting, rolling, singing Arabic phrases, which form the ethical heart of a faith and a culture. In a short video at the start of the show, we learn how these elements work together: A male voice intones one of the suras; simultaneously, an animated version of the Arabic text appears, spelled out in gold, on the screen, with an English translation below.

Once inside the show, though, we don’t have the voice, and we only occasionally have translations. What we have are the written words, which, for those of us who don’t read Arabic, we must accept as examples of text-as-design. Is that enough?

The day I was at the museum, there were just a few late-day visitors, and of those, several were women wearing hijabs. I watched them as they looked intently at the manuscripts arrayed around us, and I knew they were seeing things I couldn’t see, and feeling things I couldn’t feel, because they could read the words.

I was aware — and this is an easy perception — of the larger barriers of unknowing that stand between art and understanding, and of the barriers that stand between cultures, barriers that have, among other things, led our United States president-elect to propose banning entry to this country for women like these, who cover their heads and read a book that most of us don’t, and can’t.

Soon that president-elect will take up residence mere blocks from the Sackler. This show will still be on then. Will he see it? We can hope. But whether or not he does, some of us did, and stayed a long time, looking at, and lingering over, miraculously beautiful things and sharing, in different but not so different ways, the blessing that beauty brings.